So long, Transatlantica!

SCRIPTS Blog Post No. 64 by Jessica Gienow-Hecht

№ 64/2022 from Dec 22, 2022

For historians, it is always tempting to contemplate that everything that seems new and daring, has, in fact, already occurred before. When we consider the state of current transatlantic relations, however, the comparison with earlier periods may leave one wondering. And yet, there has been a constant critical condition in those relations that have neither vanished nor appear to do so in the near future. That condition concerns U.S. worries about a European rapprochement with or even European dependency on Russia and the Soviet Union respectively. This concern is historical, it’s been around for nearly a century and for all the global transformations of the past one hundred years, it has not changed markedly. The one thing that has changed, is the extent to which constituents in the transatlantic community are willing to go along.

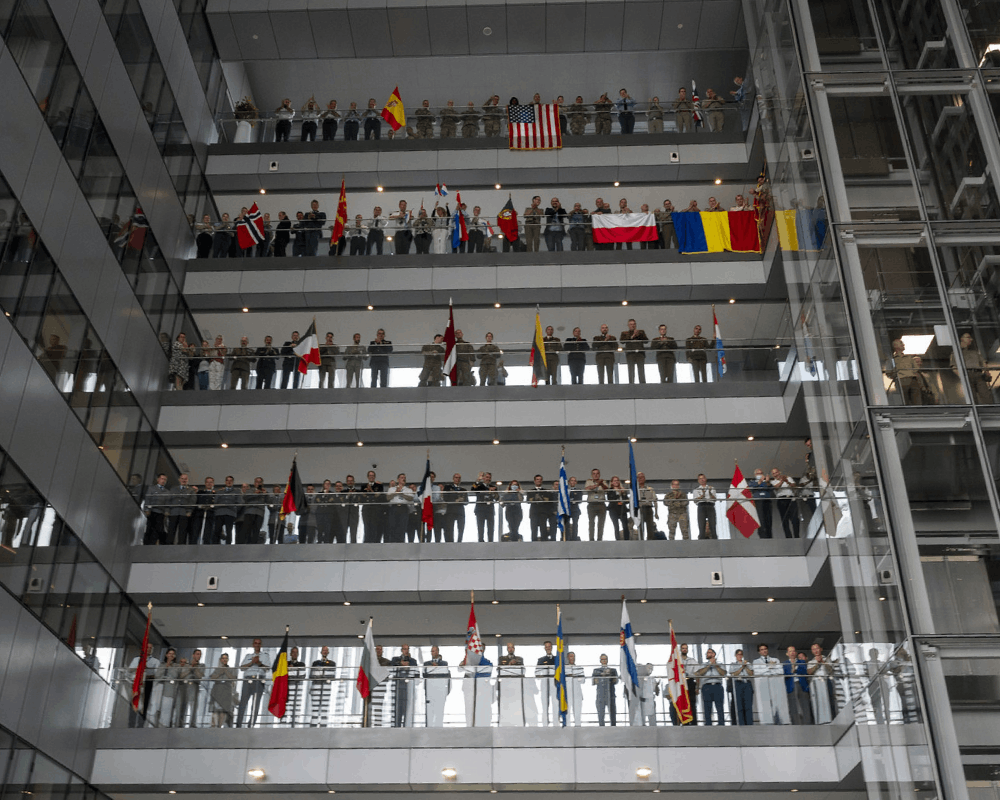

NATO International Military Staff and NATO Military Representatives in the Agora, the heart of NATO Headquarter in Brussels, Belgium on 14 July 2022

Image Credit: NATO (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) on Flickr

Transatlantic Relations after the US Congressional Elections[1]

Nostalgia

There is a long history of transatlantic relations that can be subdivided into three phases: prior to 1945 (read: World War Two); post-1945 (read: the Cold War); and post 1989/91, after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union. Prior to 1945, transatlantic relations were typically characterized by competition. Since before the turn of the century, the great powers of Europe, young and old, competed with one another for a special tie with the United States. The reasons for this were manifold but what united decision makers‘ quest for attention in London, Paris, Berlin and elsewhere was an understanding that the U.S. constituted a new kid on the block of empires, economically more attractive than politically, that one wanted to count among one’s allies. At the same time and despite two world wars, U.S. leaders did whatever they could to keep politically out of Europe – a tradition in place since the early 19th century that many felt had served the nation well. In the 1920s, there was a brief “romance“ of economic development, [1] in the words of David Engerman, during which U.S. experts seriously believed that Russian modernization would follow into the footsteps of their own country. Stalinist purges, latest, put an end to that impression to be replaced by the specter of the USSR’s “unceasing pressure for penetration,” to quote from George Kennan’s famous telegram.[2] That impression, coupled with the inter-Allied rift, became the foundation of transatlantic relations after 1945: concern about Russia. And it was one of the great achievements of postwar planners on both side of the Atlantic to replace the competitive raster of inter-European rivalry vis-à-vis the United States with stable relations between Western Europe and the United States in the context of a transatlantic alliance.

The perks and conditions of the intensive special relationship between Europe and the United States as it developed after the Marshall Plan (kicked off as the European Recovery Program, short ERP, in 1948) and the foundation of NATO (in 1949) are well known: Both were inextricably intertwined. The ERP as well as the United States’ presence and investment in Europe could only function and convince European voters and their leaders by coming along with massive security guarantees. That was the origins of NATO – a military security and alliance pact, originally, an alliance grouped around a set of values shared by new and not so new liberal democracies, and above all, a bulwark against Soviet communism.

That liaison worked beautifully throughout the Cold War. It worked because aside from deterrence, in 40 years of Cold War tension there was not a single military operation conducted by NATO. That situation has changed. Since 1992, we have seen at least seven interventions with likely more to materialize. For transatlantic relations, these interventions have been occasionally counterproductive. For one thing, interventionism from Bosnia to Syria often stirred internal opposition and controversy. For another, with every controversy, fatigue on the part of participating (financing) states increased, as did the number of critics asking difficult questions about the validity of NATO. Only partly has the war in Ukraine restrained both queries and inertia.

Generational Change

Today, the transatlantic alliance shows both signs of paralysis and loss of memory. A new generation of political actors find themselves at a loss to explain the validity, historicity, and unconditionality of those relations in a cohesive fashion. That is troubling news because we need those relations, much as they may have deviated from past models. Their future will depend on a variety of factors, four of which stand out: US domestic politics, Russia’s postwar tenure, China’s positioning in the Pacific and in Europe, as well as European strategy. (There are, of course others, such as climate control, environmentalism, conflict areas outside of NATO territory, migration, refugee crises, cybersecurity etc.).

1. U.S. domestic politics: The internal political development in the US is and will remain unpredictable and fragile. Small-scale difference in voter behavior, an increasing lack of trust in political institutions (including polls) can, today, have a huge impact on election outcomes and subsequent policy making. To be sure, foreign relations are not as controversial as are internal policies within the United States. And at least for now, the vast majority of Congress backs massive support for Ukraine. At the same time, bipartisanship is now confined to a handful of issues while domestic polarization has also entered foreign policy. And there is no denying that the U.S. as an ally appear to be increasingly built in sand. Acts signed into law as well international treaties have today a half time of about two to four years, until the next administration sweeps in.

2. U.S. foreign relations: Even though neither the end nor a clear outcome of the war in Ukraine appear to be imminent, both will have a decisive impact on transatlantic relations. In many ways, the war has played into US hands, in more than one way: It has helped to address and resolve a number of postulations raised by US policymakers that had been a burden on transatlantic relations for quite some time. Among these are the rapprochement between Germany and Russia under Merkel and Putin; the seeming lack of military burden sharing within NATO, on the part of Germany; as well as Germany’s dependency on Russian energy sources. Yet it is conceivable that in the long run, Europe’s geopolitical status will yield anew a different set of interests than the U.S. in regard to Russia, and it will have to position itself accordingly.

Related to this, Sino-American tensions will continue to affect transatlantic relations, likely even more so after the end of the war in Ukraine. China’s rise, within a generation, to a central actor in precisely that world economic order that the U.S. has always pushed for still does not sit well with many U.S. decision makers who are urging Europe to maintain distance. European countries already do face a dilemma between their midway position between China and the US, on the one hand, and their commitment to the alliance, on the other.

3. Europe: Finally, Europe’s own military, cultural and diplomatic strategy as well as its domestic policy will play a decisive role for the future of transatlantic relations. For all the programs designed to foster transatlantic identity and cohesion, Europeans today are living on the sociocultural and political investments of past generations. There is no doubt that non-state liaisons – academics, tourism, cultural exchange, business – are flourishing and will continue to ensure mutual communication, capital flow and sympathy. But there is also no doubt that the EU needs to provide citizens with a vision of leadership and who its most reliable partners will be in the future. (Note that in poll conducted the summer 2022, 71% of young Europeans demanded that EU leaders should prioritize security, even before climate change[3]).

There is not much policy makers in Brussels or Berlin can do in regard to the development of the first two points—U.S. domestic politics and diplomacy. They do, however, need to take a position on these and develop strategic answers: How will Germany and the European Union address the increasing malleability of U.S. electoral outcomes and policy making? How do they imagine Russia and European relations to Russia, post-Putin and postwar? How will they navigate the difficult balance between China and the United States? How, in short, do they envision the future of transatlantic relations beyond the status quo?

It’s the third point that is essential and this is my plea: At the end of the day, the transatlantic alliance is about, but should also be about more than an external threat on the part of a sole illiberal actor. Its future, its quality and its longevity depend, yes, on things beyond Europeans’ control but not exclusively so. To this end, Germany and Europe must, A., urgently plan and position themselves in regard to their collective future security policy. This does not necessarily entail a move outside of NATO but it does mean greater responsibility within the same. B. Both need to realize, in tandem with the United States that liberal democracies must display greater solidarity (rather than strife) on the basis of shared values. These do not merely entail wealth and geostrategic interest but liberal tenets that we share and fought for, in the past. C. Finally, European leaders need to provide young people in their respective countries with perspectives that render these values real, meaningful, and liveable: by way of employment and empowerment for the future; by way of security and international exchange; and by way of vision for a good and fulfilling life, in peace.

So long, Transatlantica!

[1] I am grateful to Thomas Risse for his comments on this blog.

[2] David Engerman, Modernization from the other Shore: American Intellectuals and the Romance of Russian Development (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004).

[3] Frank Costigliola, “Unceasing Pressure for Penetration: Gender, Pathology, and Emotion in George Kennan’s Formation of the Cold War,” Journal of American History, 83, 4 (March 1997): pp. 1309–1339.

[4] Daria Kasnitz, “2022: The European Year of Youth – What do Young Europeans Think About the EU?”, 14 July 2022, New Perspectives on Global and European Dynamics, BertelsmannStiftung, https://globaleurope.eu/europes-future/2022-the-european-year-of-youth-what-do-young-europeans-think-about-the-eu/.

Prof. Dr. Jessica Gienow-Hecht is a Principal Investigator at SCRIPTS, professor of history, and chair of the department of history at the John F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies at the Freie Universität Berlin.