What is Freedom? Some Thoughts on Masks, Reasons, Flying, Work, Lawsuits, and Inequality

by Tully Rector

№ 2/2020 from Sep 15, 2020

Tully Rector

On August 1st, around 20,000 people gathered in Berlin to protest the various measures taken by the German government to halt the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Organizers called it the Tag der Freiheit. Polling suggests that most Germans disapproved of the protest, but they understood what it was about. Securing public health requires, in this case, highly unusual and extensive restrictions, so a state imposing them can expect a measure of dissent. On camera the protestors vented various opinions: some questioned the calculus of risk, or whether government had the relevant authority, while others doubted the scientific facts and indulged in lurid conspiratorial fantasies. All relied, however, on the vocabulary of freedom, voiced in a familiar populist temper. Having to wear masks, shutter schools and business, keep your distance, refrain from traveling and partying and congregating—these represented further losses of popular sovereignty. So if we believe that the government was correct, both in substance and procedure, to act as it did, for reasons that are pretty easy to understand and endorse, we can’t help but wonder why a nontrivial number of people are willing to mass together and risk contagion to defy and denounce measures that protect their vital interests. Let’s take them at their word—it has to do with freedom.

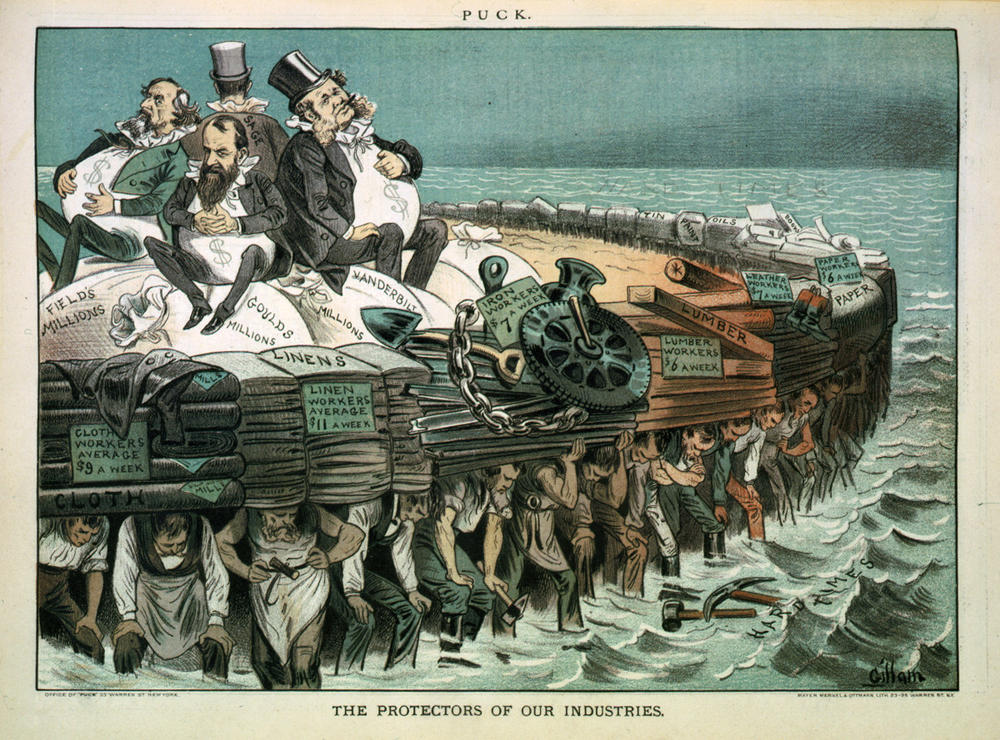

The Protectors of our Industries

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

This is among the first questions in philosophy. What does it mean to be free? Addicts, prisoners, the tyrannized and indebted, anyone caught in a loveless relationship; some have to bear more of the question’s force, but nobody can evade it, try as they might. Everyone acts. Freedom is a property of actions, of the will, of the person from whose will an action flows, and of the society in which a person occupies roles, is habituated into practices, and generally becomes who they are in relation to the actions they can and cannot undertake. As a property of social ordering, it is a political value. In liberalism it is said to be the primary value. Conflicts in liberal communities, therefore, are often clarified by examining what people are talking about when they talk about freedom. I’ll attempt that here, by going over some philosophical and political basics. It pays to recall what a philosopher back in the 60s, when new freedoms were on everybody’s mind, called the “triadic relation.” The relation holds between whoever is free (or not), what it is they’re free to do or become (or not), and that with respect to which, or on account of which, they are free to do and become it (or not).[1] I think this relation has a lot to do with reasons.

Say you’re forced to wear a mask in public buildings. A cop will throw you out and fine you for refusing. If you support the rule, and would gladly wear a mask without being forced, it’s strange to regard the rule as having compromised your freedom, but if you think wearing masks is bad and wrong, the rule has either reduced your freedom pro tanto (philosophese for: “to that extent”) or reduced it all things considered, in a way that supports a complaint in freedom. Such complaints are demands for, or rejections of, a public justification. Suppose one has been provided: public health. For the justification to succeed, at least three conditions have to be met. (1) It must really be the case that the mask rule is an effective way of preventing deadly viral contagion; (2) the government is or should be authorized to prevent such contagions; (3) complying with the rule isn’t unduly burdensome. Assume these conditions are met. If a group of protestors doesn’t accept the justification, they are in error, which means we don’t have to take their complaint seriously, even if we’re obligated to take them seriously. More on that later. The important thing is that the joint truth of (1-3) doesn’t only answer the complaint, it negates it. Freedom’s precondition is the ability to form and act on intentions, intentions to do or be something, and viral pandemics compromise that ability; the sick can’t realize their aims, and neither can the healthy when too many others are sick.

You may lack the ability to ϕ (in philosophese, the Greek letter phi is used to represent a generic action), but whether that makes you unfree to ϕ has to do with the third part of the triad mentioned above. Why can’t you ϕ? Say ϕ-ing is flying. Facts about biophysical causality explain why, as a primate, you can’t fly. Birds can do it, you can’t. You need to take an airplane. Different sorts of facts—facts about reasons—explain why you’re unable to board an airplane when wildly drunk or intending to hijack it. Others will deliberately obstruct you. The difference between being too drunk or threatening to board an airplane, and being unable to board because you’re wearing a niqab, or are praying quietly in a language unfamiliar to the airline employees, is a difference between reasons. This is the real precinct of freedom. Our inability to flap our pectoral appendages and fly has nothing to do with freedom, because no agency, human or otherwise, made us wingless. It’s all about causes, not about reasons.[2] The drunk’s inability to fly has to do with freedom, but he has no complaint in freedom, while the lady in the niqab does. Whoever obstructs the drunk acts upon considerations that favor obstruction: i.e., the welfare of other passengers. Whoever obstructs the lady acts upon considerations that don’t logically support the obstruction: i.e., religious identity. The drunk will probably wake up the next morning and feel unwell, but not unfree. He’ll see the reasons for his having been obstructed as sensible. The lady in the niqab probably won’t, and, more importantly, she shouldn’t. To come to share the reasons guiding your oppressors is to be oppressed twice over. That those reasons are reasons of the wrong type is what makes us see the obstruction of her action as oppressive.

For an action to belong inside the province of freedom, there must be considerations that do or do not favor it. When you do something freely, you do it on the basis of, or for the sake of, reasons that yo can inspect, think clearly about, and endorse. That means we’ve got two problems. One is figuring out which considerations do or not support some specific action. Another is figuring out what we should do when people disagree about what those considerations are. Political theories, like liberalism, are devised to help us with that. Notice, however, that in trying to figure out which acts would settle the disagreement over reasons in a way we could endorse, we’re trying to figure out which reasons support which actions, which has the same kind of structure as the first problem. Notice also that nobody can become a reasoner on their own. Others teach us — as teachers, good models, helpers, obstructors, cautionary tales — how to find and process what our reasons for action are. Only as social agents can we learn to see ourselves in what we think, do, and are. So any story about freedom has to connect the level of self-recognition, the story about an agent and her reasons, with a story about those relations of dependence and independence within which our options for action appear, together with the various explanations that attract or repel us, that make sense to us, or that work for you but not for me. Societies flourish when there is enough mutual intelligibility among their members to keep their coordinations fluent, their cooperative projects afloat. Their patterns of sense-making must be close enough that they can recognize one another as entitled to act as they choose, for the reasons they have. In doing so, they recognize one another as free. That recognition, when institutionally realized, helps make it true that they are free.

The August 1st protests don’t reflect a difference in what people care about. Everybody cares about their freedom. They reflect, rather, a troubling difference in what people regard as intelligible reasons for action and belief, and therefore a deeper difference, more troubling still, in their understanding of freedom. I’ve tried to say something about how these connect. The idea that SARS-CoV-2 doesn’t exist, or was unleashed by Bill Gates in an attempt to control us, or that governments aren’t entitled to enforce basic public health measures — none of these, as propositions about the world, should be taken seriously. But we should take seriously those who take them seriously. We have to figure out why large numbers of people have trouble experiencing themselves, experiencing their agency, as free, even if — or especially when — their freedom isn’t compromised in the way they say it is. How do we figure that out? We start by acknowledging that if our shared discourse — our liberal “common sense” — classifies what are, in fact, forms of unfreedom as fate, bad luck, misfortune, or, worst of all, as justice, or as freedom’s true realization, people will have false beliefs and distorted intuitions about their lives as agents. When, say, poverty looks like liberty, wearing masks looks like slavery.

Is our common sense wrong about freedom, at least in part? I think so. And nowhere more than in the economy. The opposite of freedom is servitude, domination. You’re dominated when the reasons for your action are not your own, in the relevant sense. What is that sense? Crudely: a reason is your own when you can see for yourself the value of the action it recommends, when the action’s worth, or the good it will bring about, is what shapes your choice to do it, when you choose to do it. Your reasons aren’t your own — surprise — when they’re somebody else’s. When their plans, preferences, dispositions, and so on, usurp or commandeer or replace your own, because of their power to affect your situation, to withhold or grant something you can’t help but value. The Congolese boy scratches coltan out of the pit not because iPhones are useful (though they are), but because unless he does it, his paymaster won’t give him the 2€ a day he needs to survive. The American telemarketer cold-calls people not because it makes sense to disturb them (it doesn’t), but because he’ll lose his health insurance if the company fires him for not meeting his quota. The German company’s managers lower employee benefits, replace people with robots, or move production elsewhere, not because the workers deserve to be harmed (they don’t), but because the managers will lose their own money and status if they don’t increase profits. I challenge the reader to look at the jobs most people do, the choices they have with respect to—and within—those jobs, the reasons for which they do them, and the circumstances in which those reasons are formed. How much power do people really have to set and pursue their own worthwhile aims? Are dominated people respected by those with power over them? The questions answer themselves.

Lest we think economic unfreedom is only an individual affair, consider another feature of the recent crisis. Multinational companies are poised to sue governments for revenue lost as a consequence of the public health restrictions. The global economy is structured by a nexus of trade agreements, whose ISDS (Investor State Dispute Settlement) clauses can penalize communities for imposing measures to protect health, even when those measures are recognized by the investors themselves as legitimate responses to national emergencies.[3] Add this to other, more familiar examples of corporate power: threatening capital flight, lobbying for looser rules and lower taxes, funding campaigns and other political operations, paying think tanks and university academics to generate favorable “research”, using advanced neuropsychology to promote addictive behaviors, etc. Against such power, how free are people to act in concert, as a community, for the good reasons they share? Those reasons stem from what is valued. Something is valuable that meets our needs and serves our goals, when those needs are real, those goals worth having. Deploying capital is crucial, directly or indirectly, to our needs and goals being met. The private power to grant or withhold capital is, therefore, a power to shape our reasons. It’s a power over freedom, and against it.

Until we acknowledge this fact, and find a way of institutionalizing that knowledge, people will continue to lack power over their work. Which means they’ll lack power over their time, their actions, their choices, their reasons. They’ll go on feeling and being disrespected. They won’t see themselves in what they do. They’ll see less of themselves in their laws and institutions. Why would they make sacrifices for a society that doesn’t systematically recognize their reasons for action? Why would they freely treat one another’s good as something good in itself? That’s a losing strategy in the market. At best, markets structured by private capital make the satisfaction of another’s preferences—never mind what’s really good for them—only instrumentally valuable, as a way to get what you want in exchange. In the real world, as opposed to the frictionless fantasies of neoclassical economics, such markets are machines for generating material inequality; that is, in a way, their point. Vulnerabilities are to be taken advantage of, not repaired. This is consistent with the observation that markets also promote technical innovation. They allocate rationally, but distribute irrationally. It is one thing to make useful goods, or wealth, and another to ensure they get into the hands of people who need them. So it’s pretty hard to see how a social formation organized around such markets—one that serves them, as opposed to contains them—can realize the freedoms people can’t help but value. And it’s even harder to see how, in such a society, you could effectively limit the outsize power of market winners, stop them from converting it into political authority, especially when systems are fragile, resources dwindling, profitability falling, ecosystems collapsing. It’s possible, of course, that crises like this one will clarify what our freedom really amounts to. I guess we’ll find out.

Tully Rector was a postdoctoral fellow at the International Research College at SCRIPTS, Freie Universität Berlin.

[1] MacCallum, Gerald C. "Negative and Positive Freedom". The Philosophical Review 76:3 (1967)

[2] Incidentally, that’s why it really matters whether you think God exists, or exists as some sort of agent—matters for how you think about freedom, that is—and why, as a result, changes to a society’s shared religious understanding bear tremendously upon its political life.

[3] In an advisory memo to its corporate clients, the international law firm Ropes and Gray reminded them that “notwithstanding their legitimacy, these measures (to protect health—TR) can negatively impact businesses by reducing profitability,” triggering ISDS claims that “apply even when government measures are implemented to respond to national emergencies like COVID-19.” See https://www.ropesgray.com/en/newsroom/alerts/2020/04/COVID-19-Measures-Leveraging-Investment-Agreements-to- Protect-Foreign-Investments. See also “Global firms expected to sue UK for coronavirus losses,” The Guardian, 15 August 2020.