Support in Principle, Dissatisfaction in Practice: Is There a Legitimacy Gap in Liberal Democracies?

SCRIPTS Blog Post No. 78 by Heiko Giebler

№ 78/2025 from Nov 03, 2025

Many citizens across the world continue to endorse liberal principles, yet they express dissatisfaction with how their political systems perform—even in established liberal democracies. Drawing on findings from the PALS survey, this post looks at how support for liberal principles can coexist with dissatisfaction towards liberal democracies at work—and why this legitimacy gap matters.

At a time when democratic backsliding and populist discontent dominate headlines, let me start with an oversimplification: to endure, all political regimes need to be seen as legitimate by a substantial proportion of their people. This is even true for autocracies. As history shows, repression, clientelism, and co-optation have clear limits, especially when regimes are unable to evolve within their own paradigms—as, for example, China seems to be when looking at its modernization path. What generates legitimacy, of course, varies depending on the underlying logic of a regime type. It can include archaic ideas of superiority to justify the rule of certain families in a monarchy, charismatic leadership in its original sense in theocracies, or economic prosperity in autocracies like Singapore. In liberal political regimes, often referred to and existing as liberal democracies, legitimacy beliefs are closely linked to (the fulfilment of) certain principles, e.g., individual self-determination, civil liberties, markets, rationality, and equal access to political power.

Consequently, if a monarchy’s ruling bloodline is no longer seen as superior, satisfaction with the regime and its legitimacy will decline. Translating this to current events, contestation of liberal democracies might be rooted in what citizens think about the regime. There are at least two ways in which such a regime could lose legitimacy: citizens may not support liberal principles, or citizens may not believe that these principles are actually put into practice. Hence, dissatisfaction as a driver of the crisis of liberal democracies can be based on external contestation, meaning that citizens with illiberal values do not accept the regime’s legitimacy. At the same time, it can be based on internal contestation, as citizens with strong support for liberal values do not perceive the political regime as liberal enough. Dissatisfaction then stems from unfinished liberalisation or broken promises. The resulting dissatisfaction and decreased legitimacy beliefs can destabilise political regimes.

When Believers Turn Critical: The Roots of Democratic Dissatisfaction

Using a second oversimplification in the form of an example: are current challenges to liberal democracy in Germany primarily the result of authoritarian citizens becoming more dissatisfied with Germany being a liberal democracy, or are liberal citizens less and less convinced that Germany is a proper liberal democracy? More importantly, are there general patterns across other countries around the globe?

Understanding which form dominates requires more than anecdotes—it needs data on how citizens think about both liberal principles and their political system. We can take a closer look at this with the help of the “Public Attitudes towards the Liberal Script” (PALS) survey. PALS is a comparative research project that explores support for liberal principles and institutions in the political, economic, and social spheres. Between 2021 and 2023, PALS collected data from 30 countries and 60,000 respondents across two waves. The data are representative of each country’s population and include countries from all world regions, with a wide variety of political, social, and economic contexts. The data are freely available, and there is also the PALS Data Navigator, designed to help users explore for themselves what people around the world think about liberal principles and institutions.

These data allow the construction of a theoretically grounded, encompassing measure of support for liberal principles—the Liberal Script Index (LSI).[1] They also provide information on how satisfied citizens are with the working of the current political regime.

Liberalism Without Satisfaction? What the PALS Data Tell Us

First and foremost, the PALS data show that liberal principles enjoy at least moderate support across most societies when looking at the LSI. There is no coherent external contestation of liberalism in the form of any alternative script receiving broad support among citizens. Many respondents, regardless of region or regime type, agree with core liberal ideas such as those related to democracy or a market economy. This matters because it reminds us that the “crisis of liberal democracy” is not necessarily a crisis of liberalism as a normative concept.

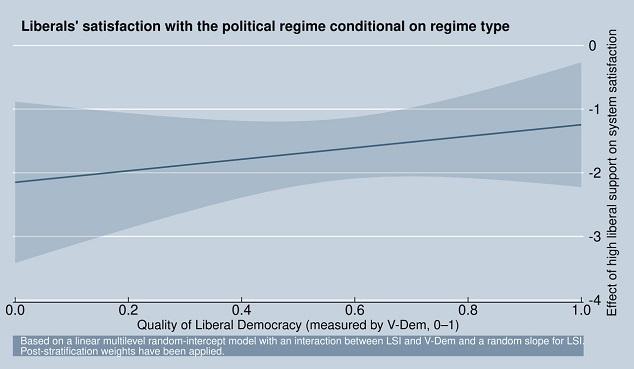

The challenge lies elsewhere—in how citizens connect these ideals to the political systems that claim to represent them. Across the 30 countries, as the figure shows, citizens who score higher on the LSI—those who most strongly endorse liberal ideas—tend to be less satisfied with how their political regimes work. This pattern is most pronounced in clearly illiberal contexts like Russia, Thailand, or Türkiye, and this is consistent with expectations (e.g., liberals should not be satisfied with Putin’s regime). Looking at the figure, these countries are located on the left-hand side representing a very low quality of liberal democracy. However, the dissatisfaction of citizens who score higher on the LSI is also present in established liberal democracies such as Chile, Germany, or Sweden. This is indicated by the fact that the effect is still negative on the right-hand side of the figure. Even after accounting for factors like age, education, or region, the pattern holds.

The irony is striking: the citizens most attached to liberal ideals are often those most disappointed by liberal democracies in practice. What does this mean more specifically? Third time’s the charm—oversimplifying again—liberal citizens are not very happy with the working of political regimes, even in countries typically classified as established liberal democracies. Hence, while it is highly unlikely that they would prefer regime change—in fact, individual self-determination as probably the core aspect of liberalism is most commonly ensured by democratic institutions—the legitimacy of liberal democracy at work seems to have taken a blow.

Obviously, legitimacy is not just about believing in liberal ideals. It is also about recognising them in everyday governance. PALS does not measure perceived implementation directly, yet the pattern it reveals—high liberal support combined with lower system satisfaction even in liberal democracies—suggests a more intricate legitimacy problem: democracies can retain believers while losing their confidence.

If external contestation is the worry, civic education, media literacy, and rule-of-law safeguards remain essential—looking at current events in the US underlines this point very well. If internal contestation is widespread, the task is different: there is a need for credible delivery on liberal promises. That means, e.g., visible progress on equal treatment before the law, fair access to political power, actual meritocracy, and institutional responsiveness. In short, defending liberal democracy against authoritarians matters—but renewing its everyday credibility by delivering on its promises may matter just as much. While there is ample legitimacy of liberal principles on which liberal democracies are supposed to be built in many countries, people are far from satisfied with actual liberal regimes. This, for sure, does not bode well for legitimacy and, consequently, the survival of liberal democracy in the long run, as dissatisfaction can be easily used as a mobilising angle for illiberal actors.

[1] The LSI was developed by Lukas Antoine, Jürgen Gerhards, Rasmus Ollroge, Michael Zürn, and me as part of a book manuscript currently under review which will hopefully be published in 2026.