Life Chances or Life Choices? Women’s Careers, Family Policy and Intergenerational Inequality in Germany

by Rona Geffen

№ 52/2022 from May 03, 2022

Rona Geffen examines the factors that determine the likelihood of women’s workforce participation. What role do family policy and social origin play in shaping women’s labor market disadvantage? There are two hypotheses explaining why women are likely to work in disadvantage and less rewarded labor market positions: The preference hypothesis suggests that women prefer to work less than men, and the socialization hypothesis maintains that women behave according to traditional gender roles which are inherited from the family of origin. Empirical findings in East and West Germany support the notion that the orientation of family policy has a tremendous impact on young women’s family socialization and career choices.

Woman and schoolgirls sit on the floor for lessons.

Image Credit: Photo by Husniati Salma on Unsplash

Women’s Opportunities in the Twenty-First Century

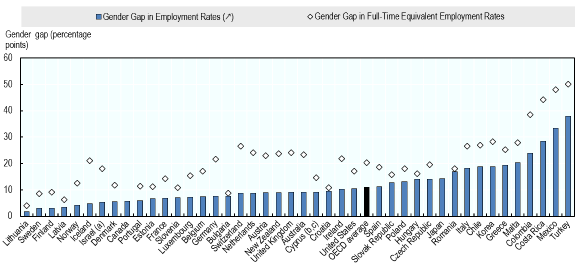

Many women in the twenty-first century have more choice, a development that is reflected in their better achievements than in the past in the areas of education, the labor market, and politics (Hakim, 2006). In European and North American countries, women’s employment rates rose dramatically between 1960 and 2000 (Scott, Crompton and Lyonette, 2010). However, gender inequalities still exist. Women are still less likely to enter the most rewarded jobs than men (Mandel and Semtonov, 2006). In 2018, the average gender gap in full-time employment rates in OECD countries was 20.3%, with only 56% of women having a full-time position (see Figure 1 below). What factors shape women’s labor market participation? Is women’s low labor market attachment due to their weaker commitment to work or is there still active structural exclusion?

Figure 1: Gender gaps in employment rates and full-time equivalent employment rates

Source: OECD Employment Database for 2018

Career Preferences or Opportunity Constraints? Explaining Women’s Economic Disadvantage

There are two main contradictory explanations to this puzzle. The preference hypothesis (Hakim, 2006) states that women in contemporary societies are free to choose their career path, including their work environment and conditions. Given that the constraints of the social structure have become less important in recent decades, young women now have the freedom to choose their work-life trajectories. Thus, the differences between women in their career trajectories are due to variations in their career preferences, leading to three groups of women: those who are career-centered and are totally committed to their work, those who are adaptive, meaning they are committed to both career and family life, and those who are non-career centered and prefer not to work.

In contrast to the preference theory, the socialization hypothesis (Crompton and Harris, 1998) maintains that women’s preferences do not explain the differences between women in their career paths, because gender norms in the social environment about the women’s and men’s normative roles influence these choices. Therefore, according to this hypothesis, women who grew up with a role model of a non-working mother tend to replicate this career behavior when they become young adults and “choose” not to work. In contrast, women with working mothers are more likely to be career-oriented and career-centered.

Family Policy, the Culture of Gender Norms, and Gender Inequality

The role of family policies is crucial in shaping or reflecting the gender norms in society, which then translate into women’s career behaviors, either through their own preferences or socialization. Family polices can be classified as more gender egalitarian, conservative, or liberal. Conservative family policies actively facilitate the combination of work and family care, but only for women, thereby maintaining gender roles and preserving gender inequalities. In contrast, gender egalitarian family policies, such as public child care, allow both men and women to combine work and family care. Thus, they are more effective in providing more choice and autonomy in these two domains and reducing gender inequality (Stier and Mandel, 2009). Unlike the conservative and gender egalitarian family polices, in the liberal family policy context, child care is generally provided privately and parental leave is limited (Gornick and Meyers, 2009). This implies that, in this context, the costs and benefits of work and family care for both men and women determine the gender division of labor, and thus, because men tend to earn more than women, the former is the main earner and the latter is the main caregiver.

In recent years, countries have started to adopt the “Adult Worker Model” as a gender egalitarian family policy that equalizes opportunities for men and women by facilitating the conditions through which they can combine work and family care. It first appeared in Scandinavian countries and then spread to other European countries, including conservative countries such as Germany (Ostner and Schmitt, 2008). This model indeed equalized the gender division of labor and thus provided more choices in work and family life for both men and women (Daly, 2011; Ostner and Schmitt, 2008).

Germany is a particularly interesting case because its family polices have changed dramatically. Although the former East and West Germany still represent different traditions of opportunity structures, after reunification, the two regions converged with regard to people’s career and family life. In the West, family policy has been traditionally conservative, reflecting by a joint tax system that fosters single-earner households, long and generous parental leave for the main care giver (usually women) and limited public child care (Rosenfeld, Trappe and Gornick, 2004). In the East, a more gender egalitarian family policy prevailed than in the West before reunification with high provision of public child care and state regulation that encouraged women’s long working hours. However, in the new reunified state, the two regions become more similar as they share one conservative family policy (Rosenfeld, Trappe and Gornick, 2004).

Since early 2000s, there was a dramatic shift in family policy in the reunified state into a more gender egalitarian family policy with the public child care expansion as well as the introduction of a shortened earning-related parental leave where two months of leave are reserved for fathers (Ziefle and Gangl 2014; Zoch and Hondralis, 2017). In spite of that, family policy is still comparatively conservative due to, among other things, the joint tax system that fosters single-earner households.

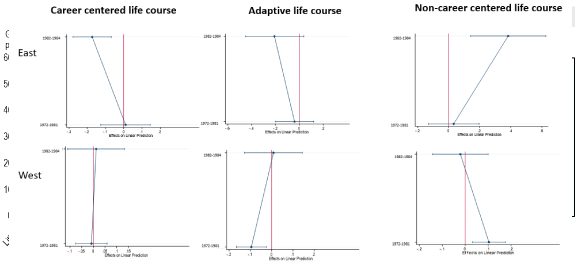

Therefore, by looking at the two historical contexts of East and West Germany, we can observe the role of the mothers’ status in shaping their daughters’ early career trajectories with respect to the change in family polices. Young women from the former East who were born in older cohorts (1972-1981) were socialized in their formative adolescence in a more gender egalitarian policy and thus, they are expected to be less influenced by their mothers’ position. In contrast, young women from recent cohorts (1982-1984) who were socialized in a comparatively more conservative social context of the reunified state have less career choice and thus they are expected to be more influenced by their mothers’ status. Following the same logic, women from the former West who were born in older cohorts (1972-1981) were exposed to more conservative family policy than those in recent cohorts (1982-1984), hence, the former are expected to be more influenced by their mothers’ status than the latter.

The findings from the German Socio-Economic Panel for a sample of women who were born in 1972-1984 and who were in ages 19-32 in the reunified Germany during 1991-2016 time frame, show empirical support for the socialization hypothesis, but only in times when family policy has been more conservative. Specifically, in both West and East Germany, the career of young women who were born in times of more gender egalitarian family policies were not influenced by their mothers’ worklessness. However, the career of young women who were born in times of conservative family policies were more influenced by mothers worklessness. Those women who grew up with workless mothers in a time of more conservative family policy are less likely to adopt a career-centered life course or an adaptive life course which combines both career and family care in East and West Germany, respectively. Instead, they are more likely to have non-career centered life course.

Interestingly, the mother worklessness effects disappear in West Germany when family policy becomes more gender egalitarian. That is, the paradigmatic shift in family policy in the direction of gender egalitarian family policies in West Germany have entirely mitigated the intergenerational transmission of disadvantage in career life between mothers and daughters. However, the increasing conservative elements in the former gender egalitarian opportunity structure in East Germany has resulted in much stronger intergenerational associations than were ever evident in the traditional context of West Germany.

Figure 2: The effect of mothers’ employment status on their daughters’ early career trajectories (workless mothers=1)

Source: GSOEP data for 1991-2016

Looking Ahead

Women in contemporary societies have more opportunities in the public sphere than in the past, but still face barriers to their career advancement. Conservative family policies shape the way daughters are socialized into gender roles within the family of origin early in life, which then structures their career “choices.” Therefore, while conservative family policies determine women’s life chances, gender egalitarian family policy opportunity structures are more effective in shaping the realization of their life choices. Without actively equalizing opportunities for men and women in the current generation, gender inequalities will persist in the next generations, which clearly undermine the liberal promises of individual advancement and equality of opportunity.

References

Crompton, Rosemary and Fiona Harris. (1998). “A Reply to Hakim”. The British Journal of Sociology, 49(1): 144-149.

Daly, Mary. 2011. “What Adult Worker Model? A Critical Look at Recent Social Policy Reform in Europe from a Gender and Family Perspective.” Social Politics 18(1): 1–23.

Gornick, Janet C., and Marcia K. Meyers. 2009. “Institutions That Support Gender Equality in Parenthood and Employment.” In Gender Equality: Transforming Family Divisions of Labor, edited by Janet C. Gornick, Marcia K. Meyers, and Erik O. Wright. London: Verso.

Hakim, Catherine. (2006). “Women, careers, and work-life preferences”. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 34 (3): 281-294.

Mandel, Hadas and Moshe Semyonov. 2006. “A Welfare State Paradox: State Interventions and Women’s Employment Opportunities in 22 Countries.” American Journal of Sociology 111 (6):1910-1949

Rosenfeld, Rachel A., Heike Trappe and Janet C. Gornick. (2004). “Gender and work in Germany: Before and After Reunification”. Annual Review of Sociology, 30:103–24

OECD Employment Database. (2018). LMF1.6 Gender differences in employment outcomes. Retrieved from: https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm

Ostner, Ilona and Christoph Schmitt. 2008.“Introduction.” In Family Policies in the Context of Family Change The Nordic Countries in Comparative Perspective, edited by Ilona Ostner Christoph Schmitt. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Scott, Jacqueline Rosemary Crompton and Clare Lyonette. (2010). “Introduction: what’s new about gender inequalities in the 21st century?”. In Gender Inequalities in the 21st Century: New Barriers and Continuing Constraints, Edited by Scott, Jacqueline, Rosemary Crompton and Clare Lyonette.DOI:https://doi.org/10.4337/9781849805568.00006

Stier, Haya and Hadas Mandel. 2009. “Inequality in the family: The institutional aspects of women’s earning contribution.” Social Science Research 38(3): 594–608.

Ziefle, Andrea and Markus Gangl. (2014). “Do Women Respond to Changes in Family Policy? A Quasi-Experimental Study of the Duration of Mothers’ Employment Interruptions in Germany.” European Sociological Review 30 (5): 562–581.

Zoch, Gundula and Irina Hondralis. (2017). “The Expansion of Low-Cost, State Subsidized Childcare Availability and Mothers’ Return-to-Work Behaviour in East and West Germany.” European Sociological Review 33 (5): 693–707.

Dr. Rona Geffen is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the International Research College (IRC) at SCRIPTS until May 2022. She holds a doctorate from the Chair for Social Stratification and Social Policy at the Goethe Universität Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Throughout her research, she explores why people’s career and family lives are persistently unequal, with a special focus on the role of social origin and the opportunity structure in shaping this inequality.